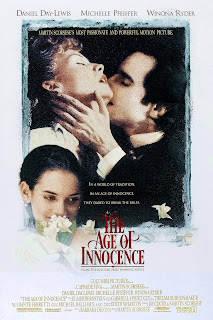

In 1993, Oscar-winning director Martin Scorsese, famed for his violent crime dramas and character studies such as Raging Bull, GoodFellas and Cape Fear, did the unthinkable: he released a PG-rated costume drama where no blood is spilled and no obscenities are uttered. Based on Edith Wharton’s landmark work of American literature, and still one of the single greatest novels in history, The Age of Innocence was a dissection of old New York society in the 1870s. Having been introduced to Scorsese via his controversial maelstrom The Last Temptation of Christ in 1988, the Blogger was as surprised as many in the industry that Scorsese would have chosen a seemingly genteel period piece, with plenty of corsets but nary a pistol in sight.

In 1993, Oscar-winning director Martin Scorsese, famed for his violent crime dramas and character studies such as Raging Bull, GoodFellas and Cape Fear, did the unthinkable: he released a PG-rated costume drama where no blood is spilled and no obscenities are uttered. Based on Edith Wharton’s landmark work of American literature, and still one of the single greatest novels in history, The Age of Innocence was a dissection of old New York society in the 1870s. Having been introduced to Scorsese via his controversial maelstrom The Last Temptation of Christ in 1988, the Blogger was as surprised as many in the industry that Scorsese would have chosen a seemingly genteel period piece, with plenty of corsets but nary a pistol in sight. What Scorsese saw in Wharton’s seminal work was apparent to those familiar with the original novel. The old way of doing battle in polite, moneyed society was not through duels and fisticuffs, but through the most powerful weapon of all: words. Wharton’s chronicle of a love triangle and its shattering effect on one man’s happiness, due to social constraint and circumstance, critiqued the old New York society in which she grew up with a knife’s edge. This was a place where the weapon of choice was good old-fashioned gossip. War was waged in salons, country homes, ballrooms and studies. It’s no wonder Scorsese was drawn to the project, because the battlefield was fraught with completely invisible landmines.

|

| Day-Lewis and Ryder, as Newland Archer and May Welland |

The triangle consists of well-to-do Manhattan lawyer Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis in the film). He is engaged to the prim and proper, but never distant, May Welland (Winona Ryder). Their forthcoming marriage would align two of New York’s most powerful and respected families. In other words, it was not so much a wedding as a power-brokered M&A. Into this world comes May’s black sheep cousin, the Countess Ellen Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer), an unconventional sort who wore black satin to her coming-out ball, married Polish nobility, and has returned to America to flee her flailing marriage. Humiliated and going through the painful motions of divorce, she is welcomed back to the fold and into society, but beneath everyone’s veneer lurks something more sinister. Countess Olenska is the subject of endless gossip and the speculation surrounding the true circumstances of her marriage’s collapse becomes the talk of the town. Newland, like a lawyer, welcomes challenges to conformity and explores them, and becomes irresistibly drawn to her. He handles her divorce proceedings while keeping his own feelings barely constrained. Rather alarmingly but discreetly, he crosses several professional boundaries by declaring his love for the Countess and she confesses to the same. The seemingly innocent May might have noticed all this going on and, if she suspects anything, she doesn’t let on easily. Wharton intended the title of her novel to be ironic, as there is nothing innocent about the comings and goings of this precariously balanced world in that day and age.

The comings and goings in old New York are marked by events on the social calendar that are carried out with considerable ceremony. There is an annual opera ball at the same wealthy benefactor’s home that follows the performance of a certain opera performed at the same time every year. Everyone goes to Boston for summer holidays, and end up staying at vacation homes within yards of their friends and neighbours. “It inevitably began in the same way: invariably”, Wharton wrotes and Joanne Woodward intones in the omniscient and ironic narrative. In a way, old New York is a collective that operates with a tribal mentality.

|

Scorsese understands that the way to draw blood from this world is not through direct combat. Most conversations in his film and in Wharton’s novel are veiled confrontations, loaded with deliberately coded wording that never exactly say what the characters want, but imply them. For instance, in one seemingly throwaway comment, May wins an archery competition, to which a moneyed observer snidely remarks, “That’s the only target she’ll ever hit”. This is a thinly disguised reference to Cupid and how she has never fully captured Newland’s heart, as the rumours are already brewing. The most succinct reference can be found in the novel described as:

"In reality they all lived in a kind of hieroglyphic world, where the real thing was never said or done or even thought, but only represented by a set of arbitrary signs; as when Mrs Welland, who knew exactly why Archer had pressed her to announced her daughter's engagement at the Beaufort ball (and had indeed expected him to do no less), yet felt obliged to simulate reluctance, and the air of having her hand forced, quite as, in the books on Primitive Man that people of advanced culture were beginning to read, the savage bride is dragged with shrieks from her parents' tent."

- Book One, Chapter 6, The Age of Innocence, Edith Wharton

- Book One, Chapter 6, The Age of Innocence, Edith Wharton

Polite society dictates that confrontations do not occur here. This is not Europe, where duels settle disputes. It’s much more discreet and sinister in America, but even if no blood is shed, one can never see the internal bleeding that causes considerable more damage.

Running in parallel to the love triangle, and as a stark contrast to their doomed love, is a subplot involving Julius Beaufort, a social climber who is considered a member of society by virtue of his marriage to a married and wealthy member of May’s extended family. He makes no secret of the fact that he has a mistress who he keeps in another part of Manhattan, and it is hinted that he made his fortune using his wife’s money as capital. When his business fails, New York shuns him and his wife is disgraced, reduced to asking May’s grandmother for financial support. As the narrator not-so-subtly states, Beaufort’s marriage guaranteed him social position “but not necessarily respect”. Although almost everyone in New York is affected by the ensuing scandal, the families speedily distance themselves from him. This serves as a cautionary tale to Newland and reminds him of his filial obligations, his promise to May, and how much he stands to lose by throwing his life away for the Countess. One does not trade honour for passion, not in that time.

|

| The disturbed glove |

This is not to say that the entire film is devoid of passion. Although this is an era in which the term “making love” meant holding hands and whispering sweet nothings in lovers’ ears, Newland and the Countess find ways to make their passions known. In an overheated sequence in a carriage after collecting her from the train station, Newland disturbs one glove button on Ellen’s finger, feels her pulse, and softly kisses it. The coiled, barely constrained passion is so vivid that the novel’s reader and the film’s viewer could practically see the blood rush through her veins. This passage communicates so much more romantic yearning than what one would see in a conventional and graphic, but passionless, “love” scene. (I make similar comment in my post on Wong Kar-Wai’s intimate portrait of romantic denial, his masterful In the Mood for Love.) It’s a testament to Wharton’s exquisite prose and to the performances by Day-Lewis and Pfeiffer that the scene smolders with incredible passion, even though almost no flesh is glimpsed. Newland’s yearning for adventure and grand romantic passion, and not the timid admiration he has for his bride-to-be, is described in this devastating passage:

"His whole future seemed suddenly to be unrolled before him; and passing down its endless emptiness he saw the dwindling figure of a man to whom nothing was ever to happen."

- Book 1, Chapter 22, The Age of Innocence, Edith Wharton

- Book 1, Chapter 22, The Age of Innocence, Edith Wharton

The film’s key performance, although it is the subtlest, is Ryder’s embodiment of May. She embodies every possible virtue desirable in a wife of that period: young, wealthy, of respectable lineage, virginal, and seemingly devoid of malice. When she realizes her upcoming marriage is under attack from enemy forces, she doesn’t make it known through obvious declarations of war or confronts anyone. Instead, she deals with it in the only way she has been conditioned: to ask through veiled but carefully crafted questions, by revealing information only she knows it to be true and to discredit others, and by playing dumb. No one would ever have accused May of being anything less than virtuous. It’s an ingenious set-up and there is a shattering revelation she reveals late in the novel and film that colours so much of what came before it that you wonder why you never saw it coming.

The theme of forbidden love has perpetually been part of public discourse and it has manifested itself throughout the ages. Around the time of the novel’s publication, a number of female writers entered “Boston marriages”, or monogamous lesbian relationships that were tolerated in certain higher circles. Interracial marriage was outlawed and eventually decriminalized throughout the twentieth century. Wharton shrewdly observed that these romantic boundaries belonged to the previous century. Nevertheless, the novel still resonates today with matches made not with the goal of perpetuating lineage or pooling assets, but speak to the grand passions across gender, age, socioeconomic, class and religious barriers. As Ian McEwen so eloquently stated in his twenty-first century landmark novel Atonement, the only thing we all want is stated by one of his character’s love for the woman from whom he is separated:

“Love you, marry you, and live without shame.”

The Age of Innocence is a film that is almost never screened in film revivals, but demands that it should be shown regularly. The lush and ample detail Scorsese lavishes on the film’s art direction and exquisite costume design (by Gabriella Pescucci, who won an Oscar for her intricate work) makes it one of the most visually ravishing films ever made. Scorsese described his scene composition as “paintbrush strokes on a canvas”. He used superimposed and edited images to flash shots of beauty, and to show the ornate detail that went into every last dinner fork on a table or the embroidery on a lace doily at a place setting during high tea. Every last detail is beautifully framed by Michael Ballhaus’s gorgeous cinematography and Elmer Bernstein’s unforgettable, weeping original score. Wharton would have approved of Scorsese’s vision and realized that it has unquestionably captured the world in which she grew up, was reared, charted, lived in and lived to expose to the world. This exposition was not unnoticed by literary critics, and Wharton for her work became the first woman in history to receive the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for her outstanding and still eminently readable work.

|

| The Countess (Pfeiffer) and Archer, locked in a moment of passion |

Scorsese received considerable praise for his film, but it has since been considered as one of his “better” if not his “best” work. This is a gross miscalculation on the part of contemporary film critics, for his Age of Innocence is one of his greatest achievements. The Blogger remembers seeing it on opening weekend in the fall of 1993 as a teenager in a jam-packed theatre, with the film presented in a luminous 70 mm print that blew out his solar plexus with its grandeur. The sound quality was so pristine that even the tiniest crackle of the fireplace sounded crisp. The film also boasts a touching cameo of his parents dressed as extras, coming out of the same train station where Newland meets Ellen and they kiss in the carriage. The film is dedicated to his father, who passed away before its release. It’s the only one of his films to contain such a dedication.

Scorsese knew the value of his work and the responsibility he bore to do Wharton’s novel justice. It’s a magnificent achievement, one that deserves to rank amongst his greatest works. The final scenes contain no words, but so much feeling, regret and memory of a lifetime's worth of soul-crushing heartache are communicated that it’s nearly unbearable. The film and the novel collectively (and even on their own) make for one of the greatest, most exquisitely painful heartbreaks of all time.