Sometimes, you hear about a film project and it’s an absolute dream. You line up a prestigious director, decorated cast consisting of award-winning actors, throw it a big budget and slot it for a prestigious holiday release, in anticipation of big box office and critical hosannas translating into a slew of show-business awards. And then sometimes it goes terribly wrong.

Sometimes, you hear about a film project and it’s an absolute dream. You line up a prestigious director, decorated cast consisting of award-winning actors, throw it a big budget and slot it for a prestigious holiday release, in anticipation of big box office and critical hosannas translating into a slew of show-business awards. And then sometimes it goes terribly wrong.

In 2008, plans were finalized for the film version of the Best Musical Tony Award-winning play Nine. It seemed to be a natural fit for a film project. The original musical was based on Federico Fellini’s classic movie 8 ½. One of the plays the original musical beat for the Tony, Dreamgirls, was adapted into a highly successful film version in 2006. Nine was meant to join the burgeoning renaissance of movie musicals, which includes not only Dreamgirls but also Moulin Rouge!, Hairspray, the Best Picture Oscar winner Chicago and Mamma Mia!, which became the highest-grossing film of all time in the UK. Nine’s glorious cast included Oscar winners Daniel Day-Lewis, Marion Cotillard, Penelope Cruz, Dame Judi Dench, Nicole Kidman and Sophia Loren, plus nominee Kate Hudson and Grammy-winning singer-rapper Fergie. The project was helmed by Rob Marshall, who shepherded Chicago to roaring success. It had the backing of The Weinstein Company, with an incredible track record of box office and Oscar winners dating back to 1992. And a sensational trailer that debuted at Cannes amidst a flurry of publicity to exhibitors and ecstatic advance word:

So why did the project fail? One could easily blame the intense box office competition at the time the film went into wide release. The blockbuster Avatar appealed to all demographics and became a cultural event, and the reboot of Sherlock Holmes, it could be argued, had siphoned the more mature audience that was meant for the sophisticated Nine. One might make the case that its failure was also owed to Up in the Air, the acclaimed dramedy that was also attracting the same crowd. Had an overabundance of films aimed at the same demographic cannibalized the audience? Sure, you could have argued that, but how does that explain why the film received mixed to dismal reviews? I was absolutely ecstatic to see the trailer in the spring of 2009, but the final project felt underwhelming when I finally caught it at a New Year’s Day matinee performance. It wasn’t from distaste for the genre, either, so that argument was out.

So why did the project fail? One could easily blame the intense box office competition at the time the film went into wide release. The blockbuster Avatar appealed to all demographics and became a cultural event, and the reboot of Sherlock Holmes, it could be argued, had siphoned the more mature audience that was meant for the sophisticated Nine. One might make the case that its failure was also owed to Up in the Air, the acclaimed dramedy that was also attracting the same crowd. Had an overabundance of films aimed at the same demographic cannibalized the audience? Sure, you could have argued that, but how does that explain why the film received mixed to dismal reviews? I was absolutely ecstatic to see the trailer in the spring of 2009, but the final project felt underwhelming when I finally caught it at a New Year’s Day matinee performance. It wasn’t from distaste for the genre, either, so that argument was out. A word on the marginal plot, taken directly from Fellini’s original 1963 film. Movie director Guido (Day-Lewis) has director’s block and is working on his latest project following a nervous breakdown. He has no script and no confirmed cast, only a leading lady (Kidman) and some sets. His loyal costume designer (Dench) has been working with him forever and wants him to do something about his procrastination. Heck, the whole movie is two hours of procrastination, set to music. He’s been cheating on his wife (Cotillard) with longtime mistress Carla (Cruz), and both come to the town where he’s filming the movie. An American journalist (Hudson) has started asking uncomfortable questions (he’s hiding his recent meltdown from the press). His mother (Loren) figures in his imagination, as does the town whore (Fergie) who introduced him to the mystique of the female gender in his boyhood. Nine concerns whether his wife ultimately wises up and leaves him, and whether or not the film is made. Neither question’s answer is at all consequential.

A word on the marginal plot, taken directly from Fellini’s original 1963 film. Movie director Guido (Day-Lewis) has director’s block and is working on his latest project following a nervous breakdown. He has no script and no confirmed cast, only a leading lady (Kidman) and some sets. His loyal costume designer (Dench) has been working with him forever and wants him to do something about his procrastination. Heck, the whole movie is two hours of procrastination, set to music. He’s been cheating on his wife (Cotillard) with longtime mistress Carla (Cruz), and both come to the town where he’s filming the movie. An American journalist (Hudson) has started asking uncomfortable questions (he’s hiding his recent meltdown from the press). His mother (Loren) figures in his imagination, as does the town whore (Fergie) who introduced him to the mystique of the female gender in his boyhood. Nine concerns whether his wife ultimately wises up and leaves him, and whether or not the film is made. Neither question’s answer is at all consequential.

What ultimately sank Nine artistically may perhaps been the fact that the source material wasn’t very good in the first place. Consider that although the original musical won the biggest prize at the Tony Awards, its Broadway run was much shorter than its competitor Dreamgirls, which played for years to rapturous audiences and has been revived so many times that it’s a now a staple of musical theatre. You remember the songs in Dreamgirls. There’s a big production number partway through that is played in the trailer (“Be Italian”), but there’s nothing really hummable or memorable about the score. Let’s face it, if you’re going to make a musical, at least have more than one decent song. Andrew Lloyd Webber, despite his being reviled by musical purists as being a populist, builds an entire score around one or two very memorable melodies that leave the theatre long after the curtain has dropped. You could hum Phantom of the Opera and Evita for days. Maury Yestin’s score for Nine is pleasant enough while you’re in the theatre watching it, but it’s not particularly hummable. A musical, for all of its production values and fancy cast, lives and dies by its songs.

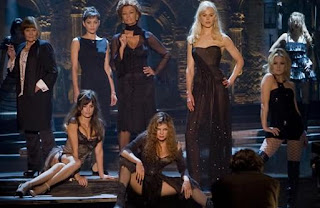

Let’s not blame the production, either. Marshall assembled most of the same crew who won or were nominated for Oscars on Chicago, and their work here is immaculate. Nine is a beautiful-looking picture, but without more substance it’s nothing more than the best kind of window display at Barneys. The cast is game, with Cruz and Cotillard as particular standouts. Day-Lewis owns the picture as he always does. Dench and Loren clearly had easy paydays, Kidman is flat, Hudson doesn’t stretch much and Fergie has the five most memorable five minutes all to herself. The cast is only as good as the material and time given to perform.

Let’s not blame the production, either. Marshall assembled most of the same crew who won or were nominated for Oscars on Chicago, and their work here is immaculate. Nine is a beautiful-looking picture, but without more substance it’s nothing more than the best kind of window display at Barneys. The cast is game, with Cruz and Cotillard as particular standouts. Day-Lewis owns the picture as he always does. Dench and Loren clearly had easy paydays, Kidman is flat, Hudson doesn’t stretch much and Fergie has the five most memorable five minutes all to herself. The cast is only as good as the material and time given to perform. The musical numbers are lavish and, but despite spending all of this time in Guido’s mind, what distinguishes the musical from the original classic film is that the flights of fancy were framed in a stream-of-consciousness format that suited the visual style very well. Fellini knew not to distinguish between reality and memory, thereby allowing the viewer to question whether or not Guido’s already lost his mind. Marshall is using the structure from the musical and applying the method that was so successful in Chicago here, but the effect is like going on holiday with a tour group where the tourists aren’t allowed to mingle with the local population: it’s an arm’s-length treatment. The performances are worth seeing, and those daydreaming of an Italian holiday could play the film without the sound, but there are plenty of other films set in Italy that have the same effect but with substance to them (The Talented Mr. Ripley, Death in Venice, Under the Tuscan Sun and even The Italian Job do the job better).

The musical numbers are lavish and, but despite spending all of this time in Guido’s mind, what distinguishes the musical from the original classic film is that the flights of fancy were framed in a stream-of-consciousness format that suited the visual style very well. Fellini knew not to distinguish between reality and memory, thereby allowing the viewer to question whether or not Guido’s already lost his mind. Marshall is using the structure from the musical and applying the method that was so successful in Chicago here, but the effect is like going on holiday with a tour group where the tourists aren’t allowed to mingle with the local population: it’s an arm’s-length treatment. The performances are worth seeing, and those daydreaming of an Italian holiday could play the film without the sound, but there are plenty of other films set in Italy that have the same effect but with substance to them (The Talented Mr. Ripley, Death in Venice, Under the Tuscan Sun and even The Italian Job do the job better).

Now, a word about the film’s title, which has nothing to do with the narrative. Fellini named 8 ½ because it was, technically, his eighth-and-a-half film, encompassing his seven features and three short subjects. The title Nine was meant to add a half-credit to Fellini’s oeuvre (although he had several more features for the next quarter-century). At best, this musical and its companion film’s contribution would only add up to a good 8¾.